In the previous lesson, we learned that we could have a function return a value back to the function’s caller. We used that to create a modular getValueFromUser function that we used in this program:

#include <iostream>

int getValueFromUser()

{

std::cout << "Enter an integer: ";

int input{};

std::cin >> input;

return input;

}

int main()

{

int num { getValueFromUser() };

std::cout << num << " doubled is: " << num * 2 << '\n';

return 0;

}However, what if we wanted to put the output line into its own function as well? You might try something like this:

#include <iostream>

int getValueFromUser()

{

std::cout << "Enter an integer: ";

int input{};

std::cin >> input;

return input;

}

// This function won't compile

void printDouble()

{

std::cout << num << " doubled is: " << num * 2 << '\n';

}

int main()

{

int num { getValueFromUser() };

printDouble();

return 0;

}This won’t compile, because function printDouble doesn’t know what identifier num is. You might try defining num as a variable inside function printDouble():

void printDouble()

{

int num{}; // we added this line

std::cout << num << " doubled is: " << num * 2 << '\n';

}While this addresses the compiler error and makes the program compile-able, the program still doesn’t work correctly (it always prints “0 doubled is: 0”). The core of the problem here is that function printDouble doesn’t have a way to access the value the user entered.

We need some way to pass the value of variable num to function printDouble so that printDouble can use that value in the function body.

Function parameters and arguments

In many cases, it is useful to be able to pass information to a function being called, so that the function has data to work with. For example, if we wanted to write a function to add two numbers, we need some way to tell the function which two numbers to add when we call it. Otherwise, how would the function know what to add? We do that via function parameters and arguments.

A function parameter is a variable used in the header of a function. Function parameters work almost identically to variables defined inside the function, but with one difference: they are initialized with a value provided by the caller of the function.

Function parameters are defined in the function header by placing them in between the parenthesis after the function name, with multiple parameters being separated by commas.

Here are some examples of functions with different numbers of parameters:

// This function takes no parameters

// It does not rely on the caller for anything

void doPrint()

{

std::cout << "In doPrint()\n";

}

// This function takes one integer parameter named x

// The caller will supply the value of x

void printValue(int x)

{

std::cout << x << '\n';

}

// This function has two integer parameters, one named x, and one named y

// The caller will supply the value of both x and y

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}An argument is a value that is passed from the caller to the function when a function call is made:

doPrint(); // this call has no arguments

printValue(6); // 6 is the argument passed to function printValue()

add(2, 3); // 2 and 3 are the arguments passed to function add()Note that multiple arguments are also separated by commas.

How parameters and arguments work together

When a function is called, all of the parameters of the function are created as variables, and the value of each of the arguments is copied into the matching parameter (using copy initialization). This process is called pass by value. Function parameters that utilize pass by value are called value parameters.

For example:

#include <iostream>

// This function has two integer parameters, one named x, and one named y

// The values of x and y are passed in by the caller

void printValues(int x, int y)

{

std::cout << x << '\n';

std::cout << y << '\n';

}

int main()

{

printValues(6, 7); // This function call has two arguments, 6 and 7

return 0;

}When function printValues is called with arguments 6 and 7, printValues‘s parameter x is created and initialized with the value of 6, and printValues‘s parameter y is created and initialized with the value of 7.

This results in the output:

6 7

Note that the number of arguments must generally match the number of function parameters, or the compiler will throw an error. The argument passed to a function can be any valid expression (as the argument is essentially just an initializer for the parameter, and initializers can be any valid expression).

Fixing our challenge program

We now have the tool we need to fix the program we presented at the top of the lesson:

#include <iostream>

int getValueFromUser()

{

std::cout << "Enter an integer: ";

int input{};

std::cin >> input;

return input;

}

void printDouble(int value) // This function now has an integer parameter

{

std::cout << value << " doubled is: " << value * 2 << '\n';

}

int main()

{

int num { getValueFromUser() };

printDouble(num);

return 0;

}In this program, variable num is first initialized with the value entered by the user. Then, function printDouble is called, and the value of argument num is copied into the value parameter of function printDouble. Function printDouble then uses the value of parameter value.

Using return values as arguments

In the above problem, we can see that variable num is only used once, to transport the return value of function getValueFromUser to the argument of the call to function printDouble.

We can simplify the above example slightly as follows:

#include <iostream>

int getValueFromUser()

{

std::cout << "Enter an integer: ";

int input{};

std::cin >> input;

return input;

}

void printDouble(int value)

{

std::cout << value << " doubled is: " << value * 2 << '\n';

}

int main()

{

printDouble(getValueFromUser());

return 0;

}Now, we’re using the return value of function getValueFromUser directly as an argument to function printDouble!

Although this program is more concise (and makes it clear that the value read by the user will be used for nothing else), you may also find this “compact syntax” a bit hard to read. If you’re more comfortable sticking with the version that uses the variable instead, that’s fine.

How parameters and return values work together

By using both parameters and a return value, we can create functions that take data as input, do some calculation with it, and return the value to the caller.

Here is an example of a very simple function that adds two numbers together and returns the result to the caller:

#include <iostream>

// add() takes two integers as parameters, and returns the result of their sum

// The values of x and y are determined by the function that calls add()

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

// main takes no parameters

int main()

{

std::cout << add(4, 5) << '\n'; // Arguments 4 and 5 are passed to function add()

return 0;

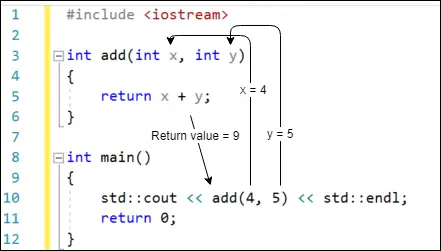

}Execution starts at the top of main. When add(4, 5) is evaluated, function add is called, with parameter x being initialized with value 4, and parameter y being initialized with value 5.

The return statement in function add evaluates x + y to produce the value 9, which is then returned back to main. This value of 9 is then sent to std::cout to be printed on the console.

Output:

9

In pictorial format:

More examples

Let’s take a look at some more function calls:

#include <iostream>

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

int multiply(int z, int w)

{

return z * w;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << add(4, 5) << '\n'; // within add() x=4, y=5, so x+y=9

std::cout << add(1 + 2, 3 * 4) << '\n'; // within add() x=3, y=12, so x+y=15

int a{ 5 };

std::cout << add(a, a) << '\n'; // evaluates (5 + 5)

std::cout << add(1, multiply(2, 3)) << '\n'; // evaluates 1 + (2 * 3)

std::cout << add(1, add(2, 3)) << '\n'; // evaluates 1 + (2 + 3)

return 0;

}This program produces the output:

9 15 10 7 6

The first statement is straightforward.

In the second statement, the arguments are expressions that get evaluated before being passed. In this case, 1 + 2 evaluates to 3, so 3 is copied to parameter x. 3 * 4 evaluates to 12, so 12 is copied to parameter y. add(3, 12) resolves to 15.

The next pair of statements is relatively easy as well:

int a{ 5 };

std::cout << add(a, a) << '\n'; // evaluates (5 + 5)In this case, add() is called where the value of a is copied into both parameters x and y. Since a has value 5, add(a, a) = add(5, 5), which resolves to value 10.

Let’s take a look at the first tricky statement in the bunch:

std::cout << add(1, multiply(2, 3)) << '\n'; // evaluates 1 + (2 * 3)When the function add is executed, the program needs to determine what the values for parameters x and y are. x is simple since we just passed it the integer 1. To get a value for parameter y, it needs to evaluate multiply(2, 3) first. The program calls multiply and initializes z = 2 and w = 3, so multiply(2, 3) returns the integer value 6. That return value of 6 can now be used to initialize the y parameter of the add function. add(1, 6) returns the integer 7, which is then passed to std::cout for printing.

Put less verbosely:

add(1, multiply(2, 3)) evaluates to add(1, 6) evaluates to 7

The following statement looks tricky because one of the arguments given to add is another call to add.

std::cout << add(1, add(2, 3)) << '\n'; // evaluates 1 + (2 + 3)But this case works exactly the same as the prior case. add(2, 3) resolves first, resulting in the return value of 5. Now it can resolve add(1, 5), which evaluates to the value 6, which is passed to std::cout for printing.

Less verbosely:

add(1, add(2, 3)) evaluates to add(1, 5) => evaluates to 6

Unreferenced parameters

In certain cases, you will encounter functions that have parameters that are not used in the body of the function. These are called unreferenced parameters.

As a trivial example:

void doSomething(int count) // warning: unreferenced parameter count

{

// This function used to do something with count but it is not used any longer

}

int main()

{

doSomething(4);

return 0;

}Just like with unused local variables, your compiler will probably warn that variable count has been defined but not used.

In a function definition, the name of a function parameter is optional. Therefore, in cases where a function parameter needs to exist but is not used in the body of the function, you can simply omit the name. A parameter without a name is called an unnamed parameter:

void doSomething(int) // ok: unnamed parameter will not generate warning

{

}The Google C++ style guide recommends using a comment to document what the unnamed parameter was:

void doSomething(int /*count*/)

{

}Author’s note

You’re probably wondering why we’d write a function that has a parameter whose value isn’t used. This happens most often in cases similar to the following:

- Let’s say we have a function with a single parameter. Later, the function is updated in some way, and the value of the parameter is no longer needed. If the now-unused function parameter were simply removed, then every existing call to the function would break (because the function call would be supplying more arguments than the function could accept). This would require us to find every call to the function and remove the unneeded argument. This might be a lot of work (and require a lot of retesting). It also might not even be possible (in cases where we did not control all of the code calling the function). So instead, we might leave the parameter as it is, and just have it do nothing.

For advanced readers

Other cases where this occurs:

- Operators

++and--have prefix and postfix variants (e.g.++foovsfoo++). An unreferenced function parameter is used to differentiate whether an overload of such an operator is for the prefix or postfix case. We cover this in lesson 21.8 -- Overloading the increment and decrement operators. - When we need to determine something from the type (rather than the value) of a type template parameter.

Author’s note

If unnamed parameters still don’t make sense to you yet, don’t worry. We’ll encounter them again in future lessons, when we have more context to explain when they are useful.

Best practice

When a function parameter exists but is not used in the body of the function, do not give it a name. You can optionally put a name inside a comment.

Conclusion

Function parameters and return values are the key mechanisms by which functions can be written in a reusable way, as it allows us to write functions that can perform tasks and return retrieved or calculated results back to the caller without knowing what the specific inputs or outputs are ahead of time.

Quiz time

Question #1

What’s wrong with this program fragment?

#include <iostream>

void multiply(int x, int y)

{

return x * y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << multiply(4, 5) << '\n';

return 0;

}Question #2

What two things are wrong with this program fragment?

#include <iostream>

int multiply(int x, int y)

{

int product { x * y };

}

int main()

{

std::cout << multiply(4) << '\n';

return 0;

}Question #3

What value does the following program print?

#include <iostream>

int add(int x, int y, int z)

{

return x + y + z;

}

int multiply(int x, int y)

{

return x * y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << multiply(add(1, 2, 3), 4) << '\n';

return 0;

}Question #4

Write a function called doubleNumber() that takes one integer parameter. The function should return double the value of the parameter.

Question #5

- Write a complete program that reads an integer from the user, doubles it using the doubleNumber() function you wrote in the previous quiz question, and then prints the doubled value out to the console.